Verb Tense and Writing Fiction

Verb tense is a very important tool in the writer’s toolbox. Will you write in the present simple and continuous? The past simple? Both?

Verb tense offers us the unlikely ability to time travel. This becomes particularly important when we explore shifting mental and emotional states of our characters. How authors depict human consciousness fascinates me. As a student of my own mind, I never tire of writers willing to explore this aspect of humanity.

Describing shifting mental states and movement through past and present can be challenging for writers. We must remain vigilant to the need to direct our reader’s attention to the right place (here) at the right time (now/yesterday/tomorrow).

(We need not worry after these details all the time. Sometimes we tell a story using straight past simple. And that’s okay. Really. Not everything need be intricate. Just as it’s fun to read a straight ahead simple romance, it’s also fun to write one. We need that sometimes, so go for it. But I also think it is invaluable for us to push our own comfort zones and use tools we’ve not used before.)

But what do we do when we the right place is in the past and the right time is the present? Why might we want to pursue this strategy as a writer?

Jean Rhys’ Good Morning, Midnight uses verb tenses to signal when Sasha Jensen’s fragile emotional and mental state. Sasha has been rescued by a friend from her room in London where she had been drinking herself to death and sent to Paris.

The City of Light overflows with memories. Indeed the novel begins with her Parisian room querying her:

‘Quite like old times,’ the room says. ‘Yes? No?’

That the street outside the room ends in a flight of stairs, ’what they call an impasse,” signals to us Sasha’s emotional and spiritual state and also tells us there will be no happy ending here.

Rhys’ hops through past and present tense with precision. Some of Sasha’s experiences of people’s hypocrisy and cruelty happen in the past, even though the framing story is told in the present. An interaction with a woman at a bar shortly after her return to Paris leads Sasha to beginning sobbing, which causes the woman to scold her.

Rhys uses the past tense here, which seems natural. We know that Sasha Rhys’ conveys this by having Sasha describe the crying incident as “That was last night.”

But Rhys wants to blur distinctions between nightmare and reality. How she does this is quite something, I think.

In a brilliant passage, in which Sasha describes a past job, she tells us about this past incident in the present tense. The past is living thing in Sasha, as it is for us. We relive with Sasha the cruel treatment from her manager.

Rhys initially frames the story in the past tense.

…it was a long white-and-gold room with a dark polished floor. Sasha begins her memory/story with a description of the beautiful woman’s dress atelier where she worked for three weeks. Her job was to greet customers and convey them to the next floor. “It was dreary.” Management forbade her from reading. “I would feel as if I were drugged, sitting there, watching those damned dolls, thinking what a success they would have made of their lives if they had been women.”

(An aside: What a brilliant image, class and gender expectations given to us in such an exquisite manner -dolls versus women.)

Sasha continues to describe a particular day at work in which the London-based managing director visited the Paris shop. She relates her thought process, again in the past tense:

“what’s he like? Oh, he’s the real English type. Very nice, very, very chic, the real English type, le businessman….I thought: ‘Oh, my God, I know now what these people mean when they say the real English type,’

and here comes Rhys performing her brilliance as we shift from the past memory to a current action/memory/story that we are all (re)living:

…He arrives. Bowler-hat, majestic trousers, oh-my-God expression, ha-ha eyes - I know him at once. He comes up the steps with Salvation behind him, looking very worried. (Salvatini is the boss of our shop).”

And so we are off. Sasha’s descent is harrowing and Rhys’ writing absolutely brilliant. We as readers become ensnared in Sasha’s teetering madness, in large part because Rhys knows when to use the past and present tenses.

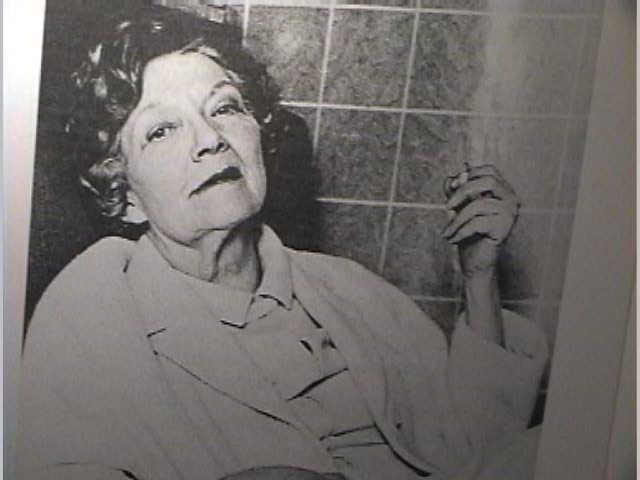

Jean Rhys for my money is a more interesting writer than Virginia Woolf. Rhys hailed from Dominica, and her mother was Creole. Her arrival to London’s high society taught her quickly about upper-crust British racism and classism and sexism. Unlike Woolf, who seemed unable to gain any distance between the world and her class standing, Rhys described upper-class cruelty with a keen, brutal eye.

Her most famous book is Wide Sargasso Sea, a prequel to Bronte’s “Jane Eyre” told from the perspective of Mrs. Rochester, the madwoman locked in Rochester’s attic so fascinating and frightening to Jane. Antoinette Cosway, a white Creole woman from Jamaica, is betrothed and married to an unnamed English husband. As their marriage progresses the unnamed husband renames her Bertha, declares her mad, confines her to the locked attic room, where she does indeed go mad.

If you haven’t read Wide Sargasso Sea, please add it to your rotation as well as Good Morning, Midnight. Rhys needed, in the words of Diana Athill, her longtime editor at André Deutsch Limited, a nanny. Athill goes on to say in the video below that despite Rhys thorough inability to care for herself, Rhys was someone worth saving. I agree with Ms. Athill. Rhys’ writing was that important.

(This video contains a super BONUS discussion from Ms. Athill about the differences between working with nonfiction and fiction writers.)