How to Read Like a Writer

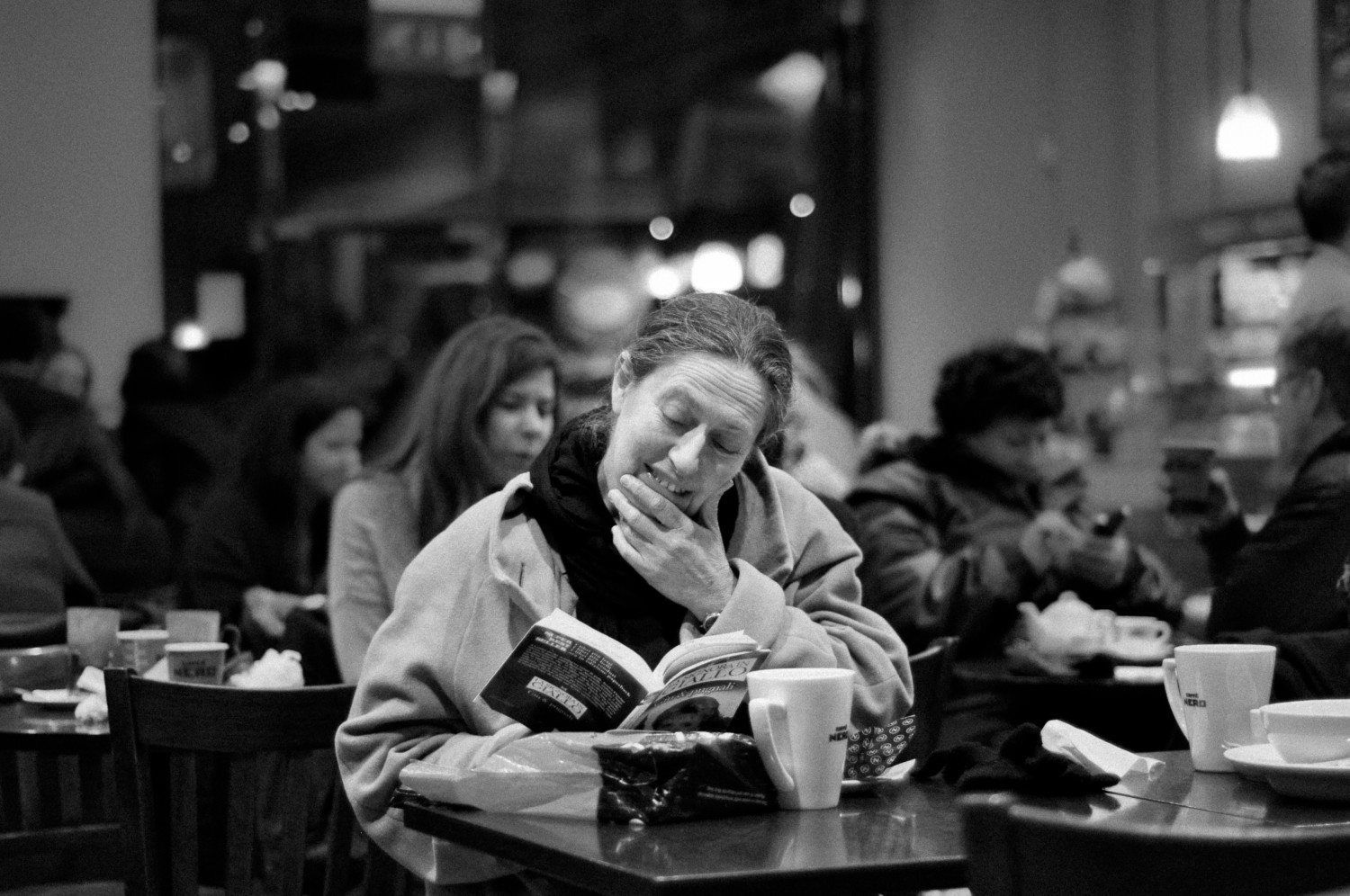

The moment when you’re reading a book…by Mendak

Reading Like a Writer Is a Writer’s Secret Weapon

When we read like a writer, we read to learn about how to write better.

Yes, we may read for understanding to better comprehend an author’s ideas, but more than that we read to understand what choices an author has made to tell the story and why. What overall structure has the author chosen? What tense did she use? What impact, if any, does the setting have on the novel? Does the author use satire or irony? If so, how?

As we read, we note the choices authors make. Then we can ask ourselves what happens to a favorite text if the author had made different choices. Holden Caufield would have been a very different character had J.D. Salinger chosen the elliptical, indirect style of Kazuo Ishiguro.

Reading for reading’s sake versus reading for writing’s sake is like admiring Coco Chanel’s fashions compared to possessing the knowledge and skill to design and sew a dress yourself while riffing on some of Coco’s tricks. Writes David Jauss:

“[R]eading won’t help you much unless you learn to read like a writer. You must look at a book the way a carpenter looks at a house someone else built, examining the details in order to see how it was made.” [1. David Jauss, “Articles of Faith” in Creative Writing in America: Theory and Pedagogy (Urbana, IL: NCTE, 1989)]

The Unreliable Narrator in When We Were Orphans

Let me share with you an example from a book I love. Christopher Banks narrates Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans. As a child both of his parents disappeared within weeks of each other while he and they were living in Shanghai.

Banks goes to great lengths to tell us a great number of times that his loss has had little impact on him. He is fine. But with great skill Ishiguro begins to undermine Bank’s narrative. An old school friend refers to Banks as “odd bird” during their time at school. Banks takes great offense at this remark. He believes himself to have been outgoing, cheery and so like other boys at school.

Another person claims Banks was a moody, withdrawn child, especially after his parents’ disappearance. Again, Banks is incensed, quite deeply actually. We begin to notice that how Banks sees himself and how others see him are quite different.

Indeed, in one telling scene, we see how far apart they are.

Banks is at wedding reception. The brother of the groom approaches him and apologizes profusely for the manner in which many of the guests have been treating him. Banks claims these people are his friends and has not taken any offense. Again the brother of the groom apologizes and tells Banks he is going to confront his abusers. Banks again claims they are his friends and that nothing is wrong.

Ishiguro’s Choice Influences His Characterization

Ishiguro chooses skillfully to never show us any of the actions or utterances of the guests. We know the brother is incensed. He is in fact quite offended by their behavior. And we know that Banks’ says repeatedly nothing is wrong. But we have no idea who said what to or about Banks.

In this scene Ishiguro has shown us the increasingly profound unreliability of Banks’ narration.

Ishiguro could have chosen to show us some of the behaviors in question. But that would have allowed us to know with certainty that Banks is a troubled and broken man. And that would have ruined the mystery at the heart of the story.

The central mystery of the story is not what happened to Banks’ parents but what has happened to Banks, and, as we begin to see how damaged he is, whether he has any hold on reality at all.

Ishiguro might have also shown us the disparity between Banks’ awareness of himself and how others perceive him through another scene. That might have worked, too. The key is that he chose not to relate any specific actions, behaviors or statements of the guests.

My takeaway of this scene is a new tool that will allow me to show an unreliable narrator or unreliable character in a natural and convincing way. This is one example, I hope, of how reading like a writer can improve your writing.