Reading Exercise: The How of Language

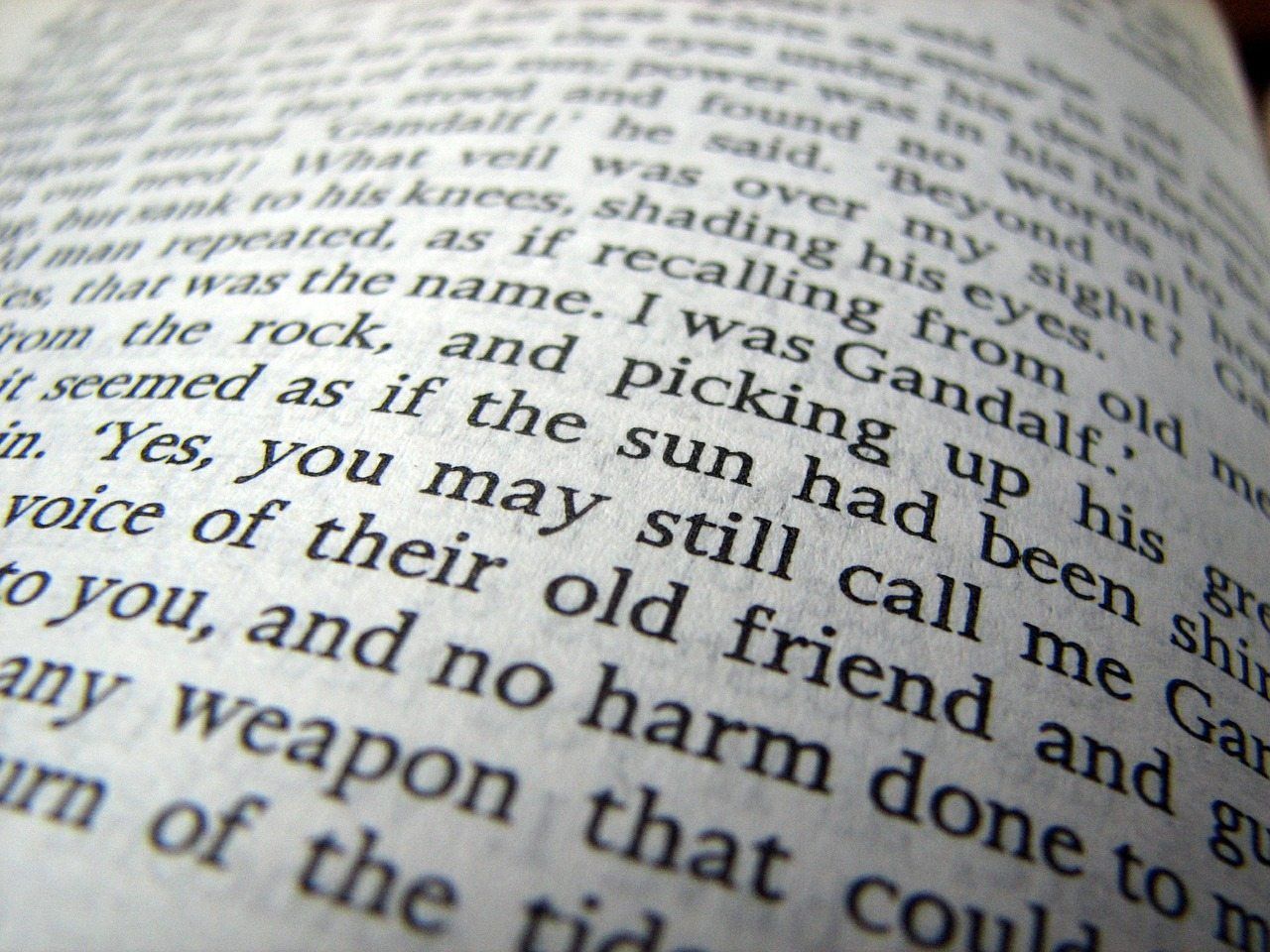

Sentences from Lord of the Rings

The how of language, argues Sven Birkets, is the sentence. [1. Sven Birkets, “What Remains,” AGNI Magazine, 69, 2009, 1-8.] This makes sense. Each writer uses sentences to create a certain style or vibe. If the author has skill, the vibe may be unique. An author with skill can also create a recognizable voice, where she can reveal what she thinks about the world.

I’ve read several novels and (a memoir) recently, all with a first person point-of-view (POV). Yet Mathias Enard’s Zone, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans offer distinct narrators simply by how they construct their sentences. Yes, Bechel’s book is a memoir. But her sentence construction, even without the tremendous graphics that accompany her sentences, can teach us something about voice and control and the how of writing.

When I read, I try to ask myself what the author has done to achieve a particular effect in me. Some things I ask myself, in addition to POV, are: What tense does the author use? How about punctuation? Does he use long, elliptical sentences or short ones with punch? Active or passive verbs?

Such studies can result in more tools I can use in my own writing.

What follows are the first several lines of each book. I would say sentences but Enard’s book is one long sentence broken up into nine chapters.

Each captures my imagination in some way. Enard’s stream of consciousness used by a character coming to terms with a brutal past contrasts with Bechdel’s relatively short sentences, controlled and tinged with sadness (but that may be me). Ishiguro’s style choices - longish, elliptical sentences - work well as he pursues philosophical questions about the nature of memory, family and friendships.

The Zone, by Mathias Enard [2. Mathias Enard, The Zone, trans. by Charlotte Mandel, (Rochester: Open Books, 2010), 5.]

everything is harder once you reach man’s estate, everything rings falser a little metallic like the sound of two bronze weapons clashing they make you come back to yourself without letting you get out of anything it’s a fine prison, you travel with a lot of things, a child you didn’t bear a little Czech crystal star a talisman beside the snow you watch melting, after the re-routing of the Gulf Stream prelude to the Ice Age, stalactites in Rome and icebergs in Egypt, it keeps raining in Milan I missed my plane I had 1,500 kilometers on the train ahead of me now I have 600 still to go

Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel [3. Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (New York: First Mariner Books, 2007), 3.]

Like many fathers, mine could occasionally be prevailed on for a spot of “airplane.” As he launched me, my full weight would fall on the pivot point between his feet and my stomach. It was discomfort well worth the rare physical contact, and certainly worth the moment of perfect balance when I soared above him.

When We Were Orphans, by Kazuo Ishiguro [4. Kazuo Ishiguro, When We Were Orphans (New York: Vintage International, 2001), 3.]

It was the summer of 1923, the summer I came down from Cambridge, when despite my aunt’s wishes that I return to Shropshire, I decided my future lay in the capital and took up a small flat at Number 14b Bedford Gardens in Kensington. I remember it now as the most wonderful of summers. After years of being surrounded by fellows, both at school and at Cambridge, I took great pleasure in my own company.

Quite a difference, yes? No particular choice is a wrong one except when the sentences work against the themes and characterizations pursued by the author.

What do you learn from your favorite authors and/or books when you write out the first few lines of each text? Anything you can incorporate in your own writing?